Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Who's in charge here anyway?

There is no good reason to be frustrated today, but I am.

It is Bear’s 11th birthday and I want to take her for a nice walk in the snowy woods. I am looking for a tranquil stroll with my dogs; a postcard moment of their black shapes weaving around tree trunks, in turns illuminated by a sinking golden sun and cast in the cool blue light of reflected white shadow.

But I feel my nerves fray with the snapping and tugging of bare branches picking at my shoulders and toque, the tips of winter-toughened twigs flicking me in the face, the cold wash of snow down the back of my neck as I duck under another beautiful tree laden in winter white finery.

The dogs have charged ahead, Murdoch leaping over downed trees and running zigzags across the trail as if he’s never seen the outdoors. Bear disappears amidst low hanging evergreens and white-blanketed saplings that swallow her up as she finds a path around obstacles. I try to keep them in my sights as I trip and stumble over deadfalls concealed beneath smooth mounds of snow.

I kind of catch up to them in the clearing at the back of our property, I can hear Murdoch crashing around somewhere in the trees. Bear has started walking up a trail that veers to the left and runs parallel to the road, eventually emerging at a sometimes-occupied house on the hill.

“Come on Bear,” I call. “We’re not going that way.” She ignores me. Her nose is stuck to the ground. I sigh. “Bear, Bear, Bear,” I say to her swaying backend as she moves slowly but deliberately away from me. She stops and looks at me. Hmmm? She seems to say, were you talking to me?

“This way Bear,” I call and wave my arm in a big arc. She turns away and continues on her original course. Murdoch appears then, flies past me as though he is being chased, and follows Bear.

“Hey,” I yell in my serious voice. “Bear, Murds, come!” They do, but in a very distracted sort of way.

I feel like I am playing catch up with the dogs as we move along the overgrown trail that runs behind our property. We are strung out like beads being slid along a wire. I find them huddled around something on the ground. They are chewing. I hope it is snow but suspect it is something left behind by a rabbit or a deer. “Come on guys. Leave it,” I yell. “That’s gross.”

They march ahead. I am invisible again. They follow trails I do not see, sparing me the odd glance as I tell them to “stick around” and “don’t go that way”. Our connection is tenuous today and it stretches and thins until we are scattered to the wind. “Come on you two,” I call into the woods, directing my words at their vague shapes poking out from behind brush and trees.

Murdoch disappears twice. I stand and listen for him, then try to hurry Bear through the trees so we can find him. She pokes along at her own pace, weaving around downed trees, distracted by smells. I stomp on dried branches in our path, splintering them under my winter boots. “This way Bear,” I say, becoming exasperated.

We step back into our own woods and I hear a faint jingle in the distance. Murdoch. I can hear him panting and then crashing and thundering. I am out of patience when we assemble again and continue on this expedition that seems to have three very distinct purposes.

Bear snuffles the ground to my left as Murdoch pounces off the trail to my right, honing in on a great big stick emerging from the snow. It is the size of a small tree limb. He swings it towards me. I put out my hands to protect my face, knock the stick away from me with my knee, but somehow my knee finds its way between Murdoch’s jaws as he clamps down a tighter grip on the stick.

“OW!!” I yell, and it echoes through the trees. He drops the stick and looks at me. Bear looks at me.

“That’s enough,” I say and dig Murdoch’s leash out of my pocket. “We’re going back to the house.” Murdoch leaps around me in a big circle at the sight of his leash as if I am taking him for a much better walk than this one.

He surges eagerly ahead on the end of his leash and I walk briskly behind him, desperate to just have a moment of calm. I look back to see Bear scooping the stick into her mouth, Wait guys! Don’t forget this! She trots down the trail to catch up to us. At the house she spits the stick at my feet with a decisive stomp. Murdoch stiffens into his ready-to-dash-in-any-direction pose.

“No,” I say and usher everyone inside.

“Why does it have to be so difficult?” I ask them as I unhook Murdoch’s leash. They have no idea what I’m talking about and as I turn to head back outside to get firewood, they clatter at my heel, determined to follow me. We knew you were only joking, they say.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Snowy morning

I watch from the window as Bear moves through our woods, a solid black shadow against the pure white of fresh snow. She picks her way slowly around gray trunks, becomes partially obscured, following the narrow path that ascends gently away from the house. She carefully investigates every inch of the white ground before her, pushing her nose down into the snow.

I am on the second floor of our house, my hands wrapped around a steaming mug of tea, looking down through the bristling branches of pine trees to follow Bear’s progress. The woods seem more tangible, more open; nooks and crannies well defined by white against not white, illuminated by an almost otherworldly glow. Bear doesn’t know I watch her and somehow I feel closer to her in that moment. And then she disappears into the thick of the forest.

We woke that morning to muted white light whispering softly in through our windows. As the sky turned from deep indigo to pale pink, the treetops visible from the third-floor bedroom windows emerged from night shadow to show us their fresh white cloaks. Until that moment I thought I was happy to not yet have any snow.

The sun, travelling much closer to the horizon now, is a smudge of cold fire behind the trees, tinging the white sky golden pink. Perfect, flat light fills the house with its gentle glow and as the wood stove ticks quietly in the entryway, time slows and the world becomes very still.

For now the snow is just a thin blanket on the ground. It coats pine boughs, outlines bare branches, defines shapes. I am still standing at the window watching the pastel sky seep its colours into the forest when Bear emerges again from the woods on a different trail. She strolls along the gentle curve of the path, stopping occasionally to snuffle at the snow.

It is relaxing to watch her quietly interact with this altered world. She moves purposefully but without hurry. Her hips sway casually with her soft footfalls, leaving a trail of wide paw prints in her wake. I stand at the window, a layer of cold air cushioning the space between me and the glass, and watch until she is directly below me, two stories down. She is cloaked in a swath of white from pushing through the spaces beneath saplings laden with snow.

I meet her at the door with a towel and sweep it the length of her body as she steps inside. The snow is partially melted and refrozen and crunches under my hands. Bear swishes her tail as I give her a quick kiss on the head, brush my hand against her cold ear and inhale the fresh, crisp smell of winter on her fur.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Remembering Sammy

March 28, 1991 – November 11, 2011

Sam was our family cat for over 20 years. But if you ever asked her she probably would have said, “What family?” Sam was completely devoted to my dad. She barely batted an eye when my sister and I left home, and greeted us with a scowl whenever we returned. My mom maintains that whenever Sammy looked at her all she saw was a tin of food with legs.

My relationship with Sam hit the dirt after the Christmas Bow Incident of 1991 and completely shattered when, years later, I showed up with Bear in tow. But it all started out so well.

The first time I saw Sammy she was three weeks old and tumbling about in a rabble with her brothers and sisters in the middle of a horse barn. I followed my parents and sister past stalls of shuffling horses to an open storage area of solid square wooden beams and warm yellow light and a floor covered in straw.

I remember a crowd of people, of voices and laughter overwhelming the space. By the time my sister and I got to kneel down beside the tiny cats most of them were spoken for. The little black and white kitten with the white spot on her back and the white-tipped tail was destined to be ours.

The barn was so quiet the day we picked her up, three weeks later. My parents and I followed a woman back to that room where the kittens had been. She pulled aside a bin, revealing the mother cat and our black and white kitten curled up together in a ball.

“She’s the last one,” she said and a bolt of sadness stabbed through my heart. How could we take away her last baby? Just look how content they are.

The mother cat stared up at us and then stood and slinked away into the shadows, leaving her kitten behind.

“Where is she going?” I asked.

“She knows you’re here for her kitten,” said the woman.

My stomach dropped as the black and white kitten blinked up at us. I quickly knelt down and plucked her from the floor, bringing her tiny body up to my neck, cradling her in my hands.

My mom named her Samantha on the way home. I sat in the back seat of the car with the kitten beside me in a small cardboard box with a folded towel on the bottom. Sam mewed and peeped and climbed out again and again, so I held my hand down to her in the box to try and keep her in one place, but she scrambled up my arm and sat on my shoulder.

After we tucked her in to her cardboard box that night I sat on my bed and listened to the plaintive cries of the tiny creature who had never been alone before. I flung open my door and in the light that spilled from my room I saw the little black and white kitten standing in the living room. She saw me and ran as fast as she could, launching herself into my arms as I knelt down, rubbing her face against mine, purring so loudly.

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Game on

I hefted the wheelbarrow stacked with firewood through the forest, bumping its fat tire up over roots and zigzagging around trees. Somewhere to my left Murdoch thundered past, I could hear him kicking up dirt, crashing over fallen trees, snapping off dead branches as he ran hidden in the shadows; behind me the determined footfalls of Bear, swishing through the leaves.

I stopped to unload the wood near the house and turned to find Bear standing inches away with a stick clamped firmly in her mouth, its stripped length protruding from between her lips like an over-long cigar. When she saw me looking at her she dropped the stick, her eyes brightened and she stomped her feet, squaring her shoulders, and backing up a few steps. Anticipation shivered through her body as she readied herself to dash off in any direction or leap straight up in the air, high enough to clear a small building.

A groaning-whine half-bark escaped her lips as I said “Okay Bear,” in an extra-calm voice, “Just one. But you have to be careful.” Bear often conveniently forgets she has bad knees. “I’ll throw it to you,” I said as I stooped to retrieve the stick from where it lay between us on the leaf-strewn ground and watched as Bear’s eyes widened, her feet stomped faster and the words I’d said bounced unheeded off her forehead.

I tossed the stick gently to her across the three-foot gap between us and she threw her front legs up in the air in a half-jump that was completely unnecessary. She snapped her jaws shut around the stick with a decisive splintering crack and then proceeded to shake her head as though she had just caught that cheeky red squirrel that chitters at her from somewhere in the pine tree by the driveway. She paraded in a circle as I finished unloading the wood.

Bear fell into step behind me again as I returned on the path through the trees to round up more wood. The empty wheelbarrow clattered and banged noisily over rocks and roots, drowning out the sounds of Bear’s feet behind me.

When we stopped, there was a moment of silent peace before Murdoch burst onto the scene like a superhero running late for the big rescue, chest puffed out, eyes ablaze as he caught sight of Bear dancing around with her stick. He cast about the forest floor and then leapt forward, dragging out from beneath the leaf litter a stick that was twice the size of Bear’s.

Bear’s jaw dropped, releasing her stick, and she sashayed over to where I stood as I took the bigger stick from Murdoch and tried to find a straight path through the trees where I could throw it.

I wound up and glanced down at the two black dogs with identical expressions of unbridled excitement plastered across their faces. “No Bear,” I said firmly. “Where’s your stick?” I pointed in the direction of her stick as I released Murdoch’s. It arced up overhead into the trees, hit some dead branches and dropped like a stone to the ground about five feet away.

Murdoch leapt and pounced and flowed around trees on the line the stick should have taken. He was a good twenty feet away when he turned at the sound of it hitting the ground and came bounding back over deadfalls and tiny saplings.

But Bear, who watched the whole thing unfold, bolted forward the minute it landed and scooped it up in her mouth just as Murdoch arrived. She turned her back sharply to him and trotted away as Murdoch grabbed the end of the stick.

Bear stormed forward, trying to wrench the stick away from Murdoch. A guttural snarling growl, hearkening back to her wild ancestors, rolled up from somewhere deep inside her and I had a flash of a fur-flying battle, white teeth bared, talon-like claws unsheathed.

But it never happened.

Murdoch let go. He actually listened to her and stood staring at me as if to say, “Well, now what am I supposed to do?” I returned his stare with a shrug as Bear trotted off the trail, propped the stick up on end against one front paw and stood chewing on the other end, spitting out chunks of wood with a certain triumphant vigour.

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

Max on the brain

Autumn reminds me of Max.

He is there in the way sun filters through the thinning canopy overhead, muted and golden, catching hints of rich browns and fine details in the trunks of poplars and firs, the pale cream on the underside of peeling birch bark.

He is in the crispness of the air; a memory of fresh, burnt autumn smells clinging to the thick mane about his neck and the warmth of his fur against my face.

I follow the narrow trail through our forest and he is there in the caramels and toffees of the leaves strewn about my feet. It is in this autumn forest that he could blend in, disappear and become larger than life at the same time.

Wood smoke drifts through the trees, a white ghostly presence shaping and reshaping itself, dispersing amongst the branches. It smells like the passage of time and I see Max curled up by the brilliant orange fire tumbling against the glass of the woodstove.

He is in the rustle of leaves, the rasp of dried marsh grasses, the breathy sweep of a raven’s wing. He is in the dazzling blue of a clear sky and the heavy gray of rolling clouds. He is in the silvery droplets of water gathered on golden leaves and the sparkling frosts of early morning.

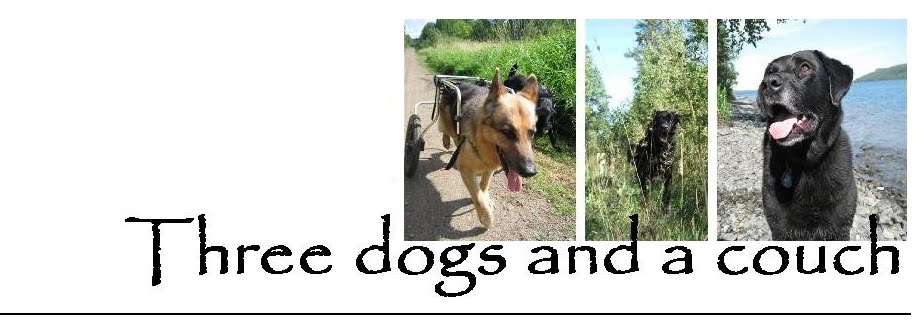

Max is everywhere, always, but in this Max-coloured autumn landscape, I see his face in everything, his kind eyes returning my stare from behind trees and amidst piles of browning leaves. Sometimes I can even imagine the squeak and trundle of his wheels behind me; the determined plod of his wide front paws defining his own path through the woods.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)